Allergies are a disease. And diseases can be cured.

The Allergy Epidemic

The numbers are staggering.

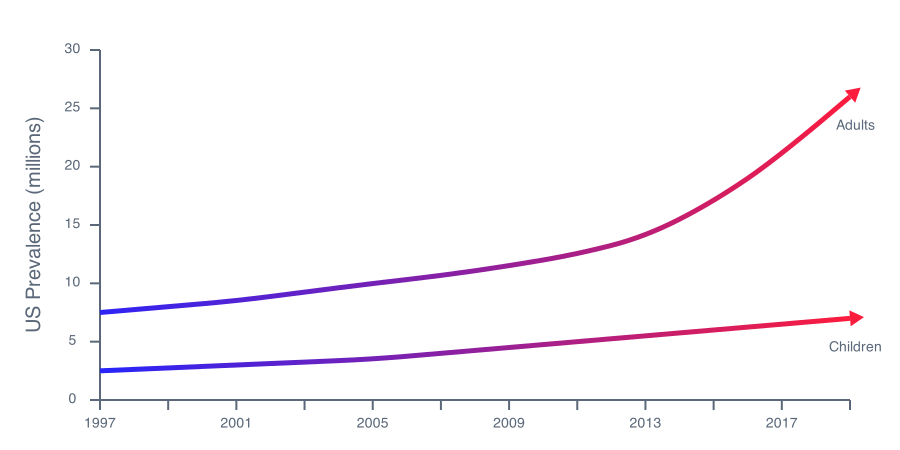

Globally, it is estimated that between 220-520 million people are living with food allergies. In the US alone that number stands at 26 million adults and nearly 6 million children. In Europe, another 11-26 million. That’s as many as 1 in 10 adults and 1 in 13 children. With numbers this high it’s clear that food allergies are now a serious public health and economic issue. Caring for children with food allergies costs US families nearly $25 billion annually.

The numbers continue to rise unabated at an unprecedented rate. To make matters worse, diagnosis and treatment options for patients and families remain severely limited, focusing on avoidance of the allergen and emergency intervention in cases of exposure. There has to be a better way.

To develop a cure, we need to understand the disease. And to understand the disease, we need to know its normal biological counterpart. Every disease is an abnormal version of some biological function.

How The Body Communicates

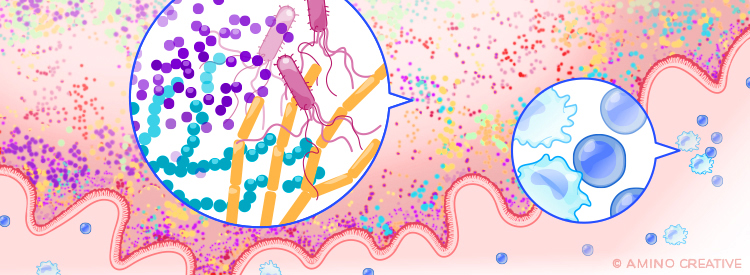

With any given bite of food, humans can be exposed to a rich diversity of natural and synthetic chemicals. Our bodies employ quality control mechanisms (primarily smell and taste) to detect potentially harmful substances and react accordingly. Our brains then use that information to determine if a defensive action is needed – such as vomiting to expel a threat. Our brains also remember sensations from threats we experience to help avoid future exposure. Surprisingly, such memories and food allergies may be connected.

Once a chemical is ingested, sensory cells in the gut continue to monitor for toxins and harmful substances, communicating with the brain and the immune system to elicit appropriate defensive responses. This includes inflammation, increased mucus production and the creation of antibodies. These antibodies are proteins custom-designed to recognize specific molecules – including antigens – and tag them so as to alert the immune and nervous systems.

Researchers have long believed that a dysregulated immune system was the major driver behind food allergies. Yet despite decades of scientific investigations rooted in the belief, we still do not fully understand why it happens. Consequently, patients are still without new diagnostics and treatments.

The Crucial Connection

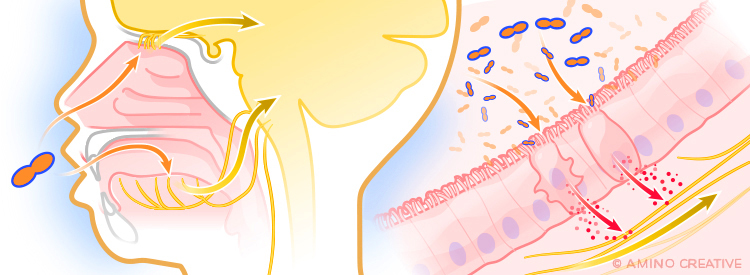

Through our work, FASI has uncovered a major new theory and research direction – the role of the nervous system in food allergies.

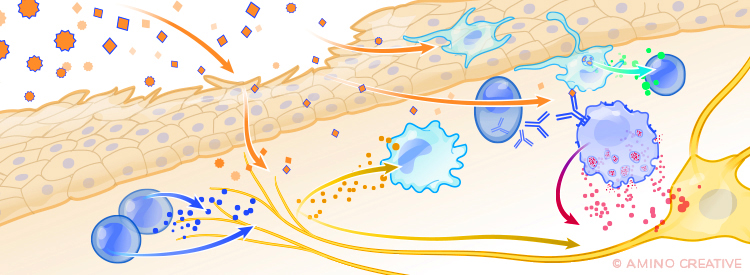

The nervous system has similar defenses and goals as the immune system. Neuronal reflexes drive common allergic reactions such as sneezing, itching, and vomiting. And jointly, the immune and nervous system evaluate food in the gut, identify allergens and trigger defense reflexes leading to an allergic reaction. We strongly believe that understanding this all-important connection between the nervous system and the immune system will lead us to the true culprits of food allergies and help us develop effective treatments before the reactions even occur. Our hope is that we can reverse our bodies from interpreting a food as a noxious substance to understanding that it’s safe for us to consume.

Using innovative genetic approaches and cutting-edge technology, we are examining how specialized cell types detect allergens and alert the body to their presence. Only once we decode these different allergen-sensing mechanisms can we develop therapeutics that block this initial detection, thus preventing allergic reactions altogether.

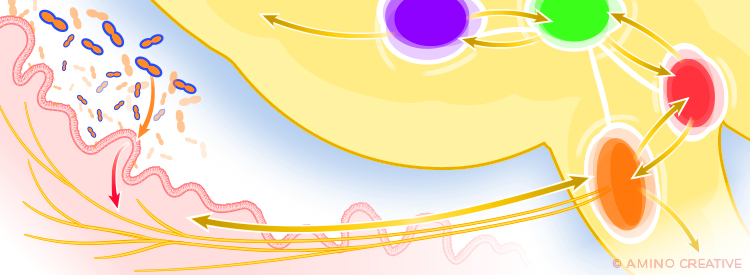

Neuroimmune communications is a major new research area in food allergy. It’s not simply an additional facet – this is the all-important checkpoint at which the body decides to either suppress or trigger an allergic reaction. The immune and nervous systems act as one functional unit to drive this decision and understanding this dynamic is critical to the development of new diagnostics and treatments.

Using experimental models of food allergy, as well as modern tools in immunology and neuroscience, we are uncovering the control of behavioral responses in food allergy. Understanding these pathways will give us crucial insights into how food allergy impacts behavior and empower the development of clinical strategies to address this in patients.

The gut’s intricate network of neurons eclipses the brain and spinal cord in size. Known as the gut’s brain, the enteric nervous system (ENS) remains poorly understood due to technical limitations. FASI scientists have developed new technologies to overcome this, and are unravelling the complex interactions of the gut, ENS and immune system to understand the pathways involved in food allergy.

Central to FASI’s vision is the recognition of food allergy as part of the body’s natural Food Quality Control system – how our immune, nervous, and digestive systems synergize to protect us from exposure to harmful compounds. Understanding these essential mechanisms shows us how they are altered in allergic disease and guides our research towards critical therapeutic targets.

FASI scientists are using state-of-the-art technologies to answer fundamental questions: how the microbiome interacts with the immune system, what role it plays in nutrient processing and allergen sensing, and how changes impact susceptibility to allergies. Making advances in these key areas opens up a new world of therapeutic potential.

Evidence points towards the involvement of the skin in allergic sensitization – but so far, we don’t know how. With obvious connections to other allergic diseases, including Atopic Dermatitis, we are investigating the role that skin neurons play in sensing allergens and driving the immune response toward allergy, revealing the key players in this important first step.

Food represents an incredibly complex mixture of chemicals derived from plants, animals and artificial sources. Our digestive system must detect both useful nutrients and potentially harmful substances. Enabled by the development of new technologies, FASI is working with partners in the food industry to evaluate a vast library of compounds and discover how they are sensed and their impact on the body.